Thomas Hardy, in Stinsford churchyard in Dorset. Have him buried in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. There was an enthusiastic campaign by the Royal Society of Literature to And 50 years after his death is a good moment to ask whether he will ever make it. Though he still has his champions (though his most vocal, his actress wife, Jill Balcon, died in 2009), he has not so far made that elusive transition into the canon of English literature. T E Lawrence recommended Day-Lewis to Winston Churchill as ‘the one great man in these lands’.

In 1934, when, with Stephen Spender and W H Auden, he was sweeping all before him as

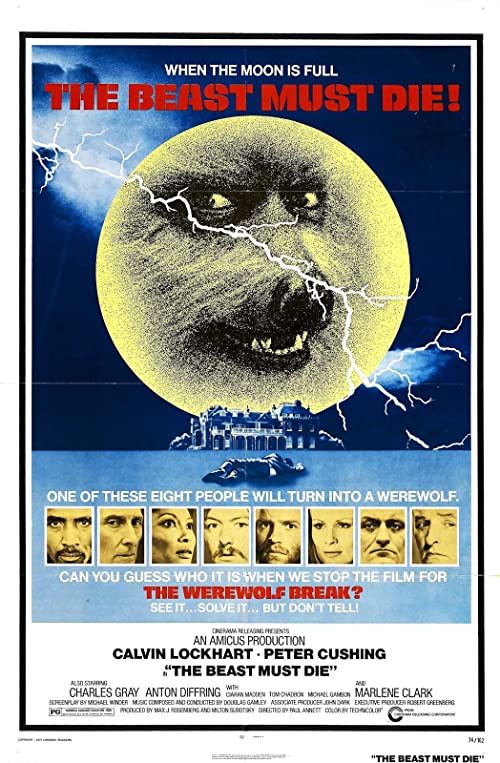

Yet for one so celebrated in his lifetime, such a harvest might be judged thin pickings. Only last year, a remake of The Beast Must Die, his 1938 crime thriller (he wrote detective fiction under the name Nicholas Blake), was translated to the small screen and won a Royal Television Society award. It’s now regularly included in public polls of the top ten poems of childhood and parenthood. Meanwhile, Walking Away, written after he dropped off his elder son, Sean, at school – with the resonant final lines, ‘selfhood begins with a walking away/And love is proved in the letting go’ – is on the GCSE syllabus. Half a century on from his death on 22nd May 1972, that same sack of genes has seen Daniel become the only three-times winner of the Oscar for Best Actor.

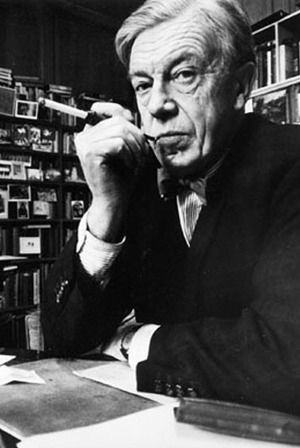

In Children Leaving Home, a poem written at the end of his life for his two younger offspring, Tamasin and Daniel, the Anglo-Irish Poet Laureate Cecil Day-Lewis (1904-72) posed the question ‘What shall I have to bequeath?’ His dispirited answer was ‘a sack of genes/I did not choose, some verse/Long out of fashion, a laurel wreath/Wilted…’

Fifty years after his death, we should salute his poetry, says Peter Stanford Cecil Day-Lewis is remembered for a scandal and his famous son.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)